I augment traditional literary analysis with Natural Language Processing (NLP) tools to compare Fyodor Dostoevsky's Rodion Raskolnikov (Crime and Punishment) with Ayn Rand's Howard Roark (The Fountainhead). Tools include both the Google Cloud Platform (GCP) Natural Language Application Programming Interface (API) and Tensorflow Transfer Learning.

I use the same approach I followed in my Thoreau vs. Unabomber blog post. The GCP NLP API measures character sentiment (positive or negative) and emotional intensity while the literary analysis frames the quantified personality metrics with relevant quotes.

My earlier post analyzed Thoreau and the Unabomber's manifestos. These texts provide single-voice narration which yielded simple data preparation. Unlike The Unabomber Manifesto and Walden, however, Crime and Punishment and The Fountainhead include multiple speakers and a narrator.

Valid analysis requires me to extract the speaking lines for Raskolnikov and Roark from their respective works. I used Tensorflow and Keras NLP to accomplish this task.

Quantify Sentiment

I take the extracted dialog and internal monologues from Raskolnikov and Roark and feed them into the Google API. The API infers sentiment (score) and intensity (magnitude).

The GCP NLP API docs define score and magnitude:

- Score

- Indicates the overall emotion of a document

- Magnitude

- Indicates how much emotional content is present within the document, and this value is often proportional to the length of the document

Open my Thoreau vs. Unabomber post in a new tab to find my script that processes the texts, emits them to the API, and records the results.

NOTE: I uploaded the Sentiment analysis data for both Raskolnikov and Roark to Github.

Import Data

Requests imports the data straight from GitHub.

import pandas as pd

import io

import requests

roark_url = 'https://github.com/hatdropper1977/Raskolnikov/raw/main/Roark/roark_sentiment.csv'

rask_url = 'https://github.com/hatdropper1977/Raskolnikov/raw/main/rask_sentiment.csv'

roark_r = requests.get(roark_url).content

rask_r = requests.get(rask_url).content

roark_df = pd.read_csv(io.StringIO(roark_r.decode('utf-8')))

rask_df = pd.read_csv(io.StringIO(rask_r.decode('utf-8')))

Numeric Analysis

Pandas extracts Roark's most negative dialog.

roark_df[ roark_df.score == roark_df.score.min()]

score magnitude text

52 -0.8 0.8 """You're wasting your time,"" said Roark."

Roark's most negative dialog: "You're wasting your time"

A similar command extracts Raskolnikov's most negative dialog. Note that Twenty Four (24) lines of dialog share the max sentiment of Negative Zero Point Eight (-0.8).

rask_df[ rask_df.score == rask_df.score.min()].size

24

For example, Raskolnikov's most negative dialog includes:

All this is very naive . . . excuse me, I should have said impudent on your part

One Dimensional Graphical Analysis

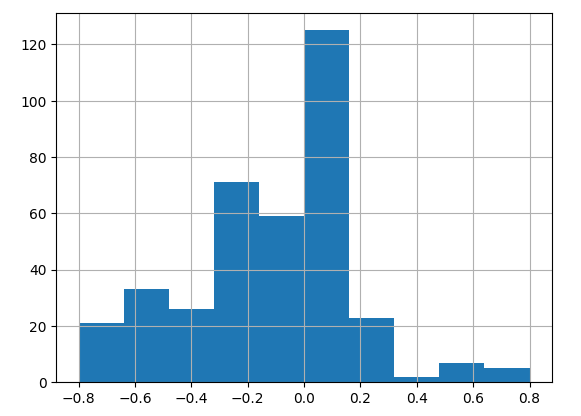

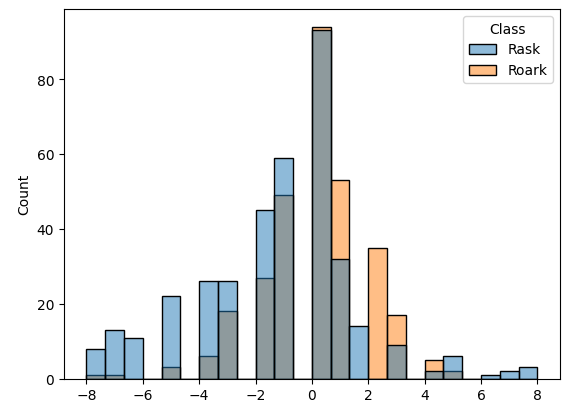

Pandas provides an easy method to generate Histograms.

rask_df['score'].hist()

Raskolnikov's sentiment histogram leans negative.

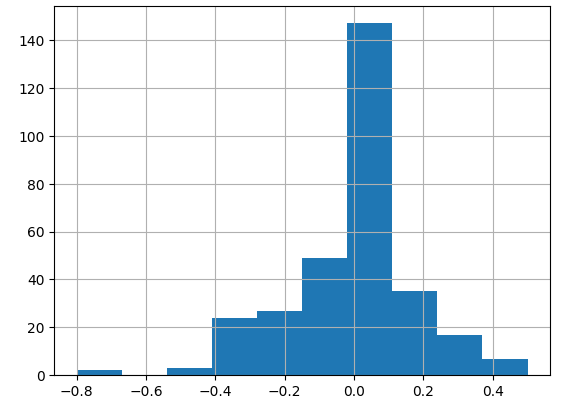

Roark's sentiment histogram spikes at neutral. His negative lines of dialog taper off, with few beyond Negative Zero Point Four (-0.4)

I use Seaborn to overlay the two Histograms.

import seaborn as sns

I concatenate the two Data Frames into one Data Frame. I add a Label column, named Class. This label allows Seaborn to color the data by Speaker.

roark_df['Class'] = 'Roark'

rask_df['Class'] = 'Rask'

sentiment_df = pd.concat([rask_df, roark_df])

I run histplot on the new Data Frame.

sns.histplot( x = sentiment_df['score'],

hue = sentiment_df['Class'])

The overlaid Histograms illustrate that Raskolnikov (Blue) leans more negative than Roark (Orange).

Two Dimensional Graphical Analysis

The Google API returns two dimensions of data: score and magnitude. The magnitude data captures the intensity of emotion.

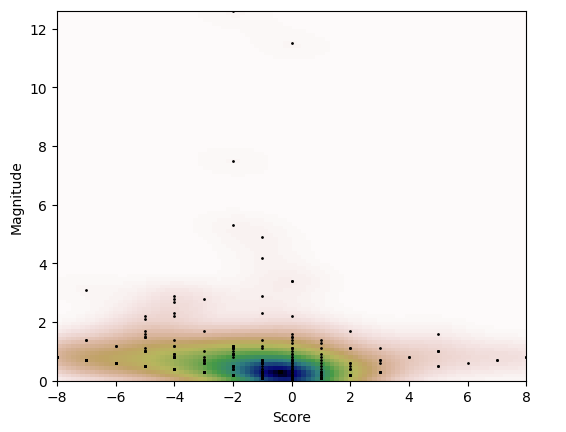

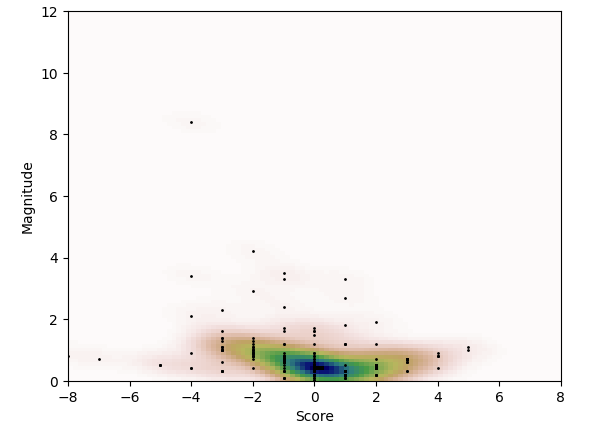

SciPy Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) generates a bivariate density plot for each speaker.

The colors represent density. Darker colors indicate more instances of a particular score/magnitude pair. The black dots represent the actual data points.

NOTE: I scale the Score by ten to improve chart readability

We know from the histogram that Raskolnikov leans negative. He reigns in the emotional intensity, however, with most of his dialog clocking in at an intensity of one (1).

Compare Raskolnikov's nearly horizontal chart to Roark's chart. Roark's chart angles up a bit in the negative zone. This upward angle indicates that Roark increases emotional intensity in lockstep with negativity. The more negative the dialog, the more intense the magnitude.

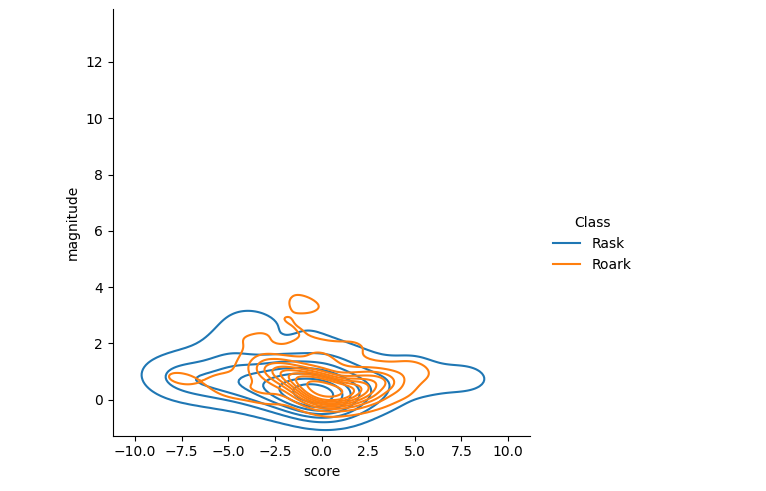

SNS once more allows us to overlay the two density plots.

sns.displot( x = sentiment_df['score']*10,

y = sentiment_df['magnitude'],

hue = sentiment_df['Class'],

kind = 'kde')

This chart captures Raskolnikov's negative sentiment with neutral intensity and Roark's slight intensity upticks.

Literary Analysis

An astute reader finds similarities between Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment, and Howard Roark, from Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead.

Rodion and Roark share misanthropic traits. Roark's creator vs. second hander hypothesis echoes Rodion's extraordinary man vs. raw materials hypothesis. Their ethics drive each to perform criminal acts of destruction.

The two characters have separate reactions to their crimes. The differences in their reactions set them apart.

Social Misanthropes

In college, Roark refuses to join a fraternity or engage in graduation festivities. Rand writes he:

never [has] any friend anywhere (Rand 253)

Peter Keating (an acquaintance of his) states:

nobody can like him (Rand 253).

Dostoyevsky writes that Raskolnikov, like Roark, enjoys:

practically no friends [and] somehow fail[s] to take any part in [other student's] communal gatherings, their discussions and their amusements, and [holds] no share in any other aspects of their lives (Dostoyevsky 85).

Raskolnikov spends his time in college:

study[ing] intensely, not sparing himself (Dostoyevsky 86)

Post-expulsion he takes a six-month hiatus from society to focus on personal philosophies. Raskolnikov's peers label him a:

haughtily arrogant [egoist] (Dostoyevsky 86).

Razumikhin, Raskolnikov's best friend, says:

He doesn't listen to what people say to him. He's never interested in what everyone else is interested in at any given moment (Dostoyevsky 265)

Pulcheria Alexandra, Rodion's mother, asks Dunya:

I mean, It couldn't be that he's an egotist, Dunechka? Eh? (Dostoyevsky 291)

Disgust Towards Parasites

Howard Roark despises collective thought. He says:

The mind is an attribute of an individual. There is no such thing as a collective brain... No man can use his brain to think for another (Rand 737)

He further states:

[Man] can survive in only one of two ways- by the independent work of his own mind or as a parasite fed by the minds of others (Rand 738)

He considers these parasites:

second handers [and] savages (Rand 742).

Raskolnikov increases the vitriol against second hand parasites. After Luzhin tries to impress Raskolnikov and Razumikhin with his ideas on progress, Raskolnikov cuts him down and says:

He learned that all by rote! He's Showing off! (Dostoyevsky 193)

Extrodinary Man vs. Egoist

Rodion subscribes to the theory of the extraordinary man and Roark to that of the egoist.

Both theories separate human society into two classes. The two protagonists champion the improvement of society through great Men who stand apart from the masses.

Rodion labels mediocre and uninspired members of the populace raw materials. His raw materials stand in for Roark's second handers.

Neither the raw materials nor second handers think for themselves and recycle old ideas. They keep the world in an evolutionary stasis. Raskolnikov states that the Raw Materials live only to:

bring into being more like itself, and another group of people who possess a gift or talent for saying something new, in their own milieu (Dostoyevsky 313)

Raskolnikov's Raw Materials live to procreate, to increase the chance of spawning Raskolnikov's extraordinary man, or Roark's egoist/ creator.

Both agree that the lesser men ostracize (or kill) the great men. Rand writes that Second Handers consider egoists:

transgressors that venture into forbidden territory (Rand 736)

Raskolnikov says that raw materials see extraordinary men:

as being persons of backward and degrading views (Dostoyevsky 315)

Difference in Execution

Roark's philosophy stresses the importance of the individual. A creator will not rely on others to survive. Society benefits when a collection of individuals focus on their own needs and align their actions with those needs:

No creator [should be] prompted by a desire to serve his brothers, for his brothers [will] reject the gift offered and that gift [will] destroy the slothful routine of their lives. His truth [should be] his only motive. His own truth, and his only motive to [should be to] achieve it in his own way (Rand 737)

Raskolnikov, however, suggests that extrodinary men must use the raw materials to their own ends:

If an extraordinary man "finds it necessary, for the sake of his idea, to step over a dead body, over a pool of blood, then he is able within his own conscience to do so. It's in this sense alone that [they have a] right to crime" (Dostoyevsky 313).

Roark stresses individual focus. Raskolnikov condones the (criminal) use of groups to reach a goal.

Roark criticizes Raskolnikov's theory. He considers Raskolnikov's conquerors second handers.

The most dreadful butchers [are] the most sincere. They believe in a perfect society through the guillotine and the firing squad. Nobody questions] their right to murder since they [are] murdering for an 'altruistic' purpose. It [is] accepted that man must be sacrificed for other men... It goes on and will go on so long as men believe that an action is good if it is unselfish. That permits the 'altruist' to act and his victims to bear it. Now observe the results of a society built on individualism. This country was not based on selfless service, sacrifice, renunciation or any precept of altruism. It was based on a man's pursuit of happiness. Not anyone else's, a private personal, selfish motive (Rand 741-42)

Both Raskolnikov and Roark act according to their beliefs. Raskolnikov's extraordinary man belief compels him to kill a pawnbroker and her sister. Roark's creator belief leads him to destroy his desecrated Cortlandt building.

Follow Through

Raskolnikov and Roark differ in their commitment to their criminal actions. Roark held to his convictions and did not experience guilt or compromise after completing a crime that upheld his ethics. He lived up to his creator principles.

Raskolnikov, however, could not justify the crime to himself. He admitted failure on several occasions before he turned himself in. He did not live up to his extraordinary man principles.

Howard Roark refuses to accept nor consider any wrongdoing. He insists that America must uphold its first principles and recognize the necessity and urgency of his (Roark's) actions. A country that compromises equals a slave society (Rand 743)

Roark says he will serve his time:

in memory and in gratitude for what my country has been. It will be my act of loyalty, my refusal to live and work in what has taken place (Rand 743).

Contrast Rodion to the stalwart Roark. Raskolnikov experiences guilt, admits failure, and contemplates suicide. He says:

I don't want to go on like this (Dostoyevsky 200)

Rodion can not muster the conviction to self-annihilate:

I wanted to end it all there, but... I couldn't bring myself to do it (Dostoyevsky 593)

Rodion admits defeat and turns himself in. He does not recognize any extraordinary man qualities in his character. He labels himself a failure:

It's because of my own baseness and mediocrity that I'm taking this step (Dostoyevsky 595).

He questions why he, a raw material, felt that he was qualified to act in the manner of an extraordinary man. He speculates:

the strength of his own desires that made him believe he was a person to whom more was allowed than others (Dostoyevsky 623)

Conclusion

Rodion and Roark see banality and mediocrity in the Common Man. They share apathy towards base men and disgust towards phony men. Their disgust incites one to become a hermit for several months and causes the other to become an object of hatred and jealousy among his peers. They both commit crimes by their beliefs. In the aftermath, Rodion folds and Roark stands strong.

Did Rand use the character Rodion to inspire Roark? If so, Rand aligns with Roark's creator principles.

Roark says:

We inherit the products of the thought of other men. We inherit the wheel. We make a cart. The cart becomes an automobile... But all through the process what we receive from others is the end product of their thinking (Rand 738)

Bibliography

- Dostoevsky, Fyodor. Crime and Punishment. Bantam Books, 1996.

- Rand, Ayn. The Fountainhead. Plume, 1994.