Freshlex LLC (should) architect the reliable multicast infrastructure for the putative John Carmack biopic, which will hit the Internet in December of 2018. The first blog post discusses two of the enabling technologies, FCAST and ALC. The second blog post discusses the remaining three technologies, LCT, WEBRC and the FEC building block. The third blog post discusses an Architecture that integrates the five technologies. This final architecture discusses possible integration issues and challenges.

WEBRC Integration Issues

Our FCAST/ALC architecture runs over a multicast IP network. An issue arises when the multicast IP network uses RFC112 Any Source Multicast (ASM). The WEBRC building block uses multicast round trip time (MRTT) and packet loss to compute a target reception rate. The WEBRC receiver uses this target reception rate for congestion control. ASM skews MRTT and packet loss, and thus gives receivers an erroneous target reception rate.

The WEBRC receiver computes MRTT as the time it takes the receiver to receive the first data packet after sending a join request to a channel. ASM, however, initiates multicast using rendezvous points (RP). All transmitters send their data packets to an RP (decided a priori by network engineers) that may be far away. The receivers send a join to this RP. Once data packets begin to flow to the receivers, the routers switch to a shortest path tree (SPT), finding the shortest path from the transmitter to the receiver, which does not need to include the RP. [RFC5775 6]

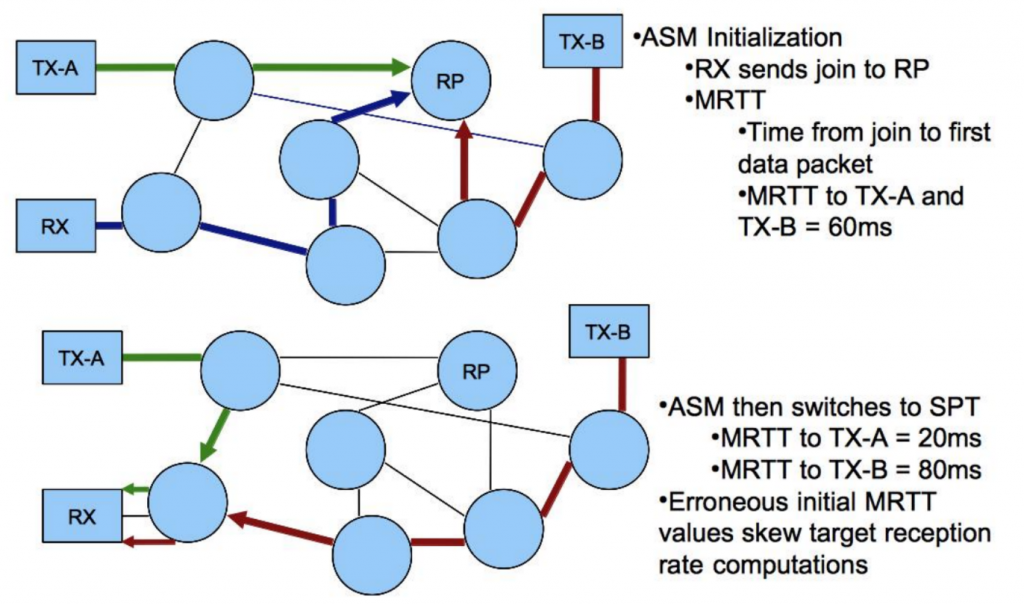

The following (see diagram) illustrates a scenario where switching from an RP to SPT skews the WEBRC receiver MRTT computation (and therefore target reception rate). We use ASM, so "any source" transmits to the multicast address. TX-A and TX-B both have data to multicast. They transmit to the rendezvous point. The RX has no idea who is sending, they just want to join the multicast, so they send a join to the rendezvous point. The RP is three hops away. Lets say for illustrative purposes each hop adds 10ms delay. The join takes 30ms to reach the RP and then the first data packets from the multicasts for TX-A and TX-B take 30ms each.

Thus, the RX computes the MRTT for TX-A as 60ms, and the MRTT for TX-B as 60ms. At this point the multicast enabled routers switch to shortest path tree. The multicast from TX-A to the RX now only takes one hop, so the MRTT would be 2 * 10ms or 20ms. The multicast from TXB to the RX is now four hops, so the actual MRTT should be 80ms. Thus, as a result of ASM, the RX sets the target reception rate for TX-A as 66% too low, and the target reception rate for TX-B as 33% too high.

The “saving grace” in the case for TX-B would be the dropped packets, since 1/3 would drop and the RX would change the target reception rate accordingly. WEBRC, however, adjusts rates at points in time that are separated by seconds. In addition, if we lost packets during the switch over from RP to SPT then the RX would have incorrect parameters for packet loss (based on receiving or not receiving monotonically increasing sequence numbers), which would skew the target reception rate. The solution to this issue is to use SSM multicast, which does not use RP. If we must use ASM, then have one RP (and thus multicast address) per sender and put the RP as close to the sender as possible (i.e. on the first hop router at the demarc). [RFC5775 6]

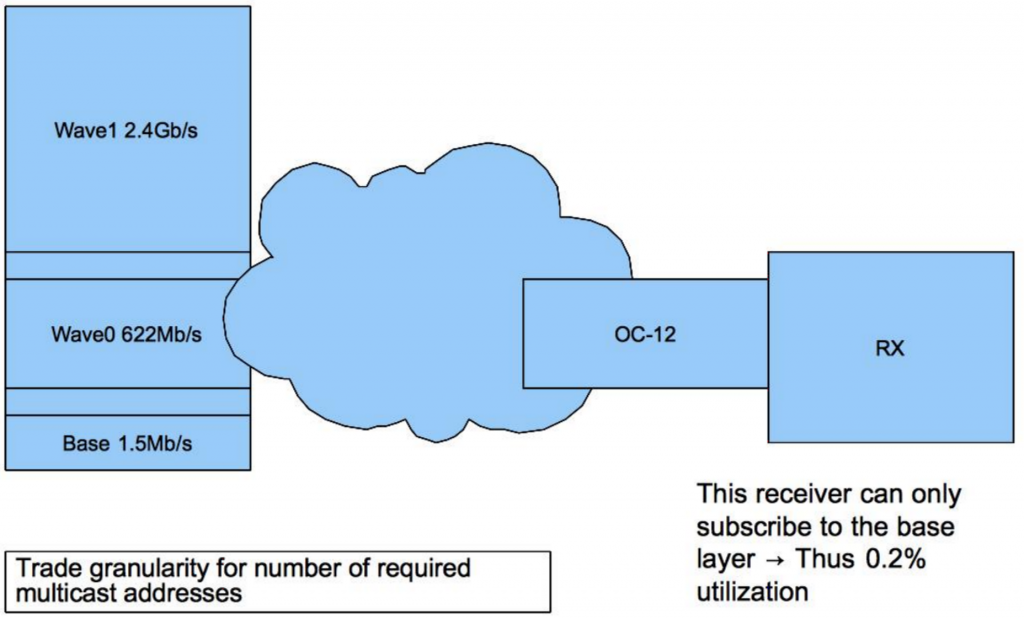

Another design issue with WEBRC deals with setting the appropriate wave channel rates. We need to set the base rate to the lowest common denominator, so that all users can subscribe to it. The main purpose of the base channel is to communicate timing information (CTSI) and wave channel rates to the receivers so they can sync their joins to wave channel periods and join enough channels to reach their target rates (RFC3738 8). We need to, however find the right balance for the wave channel data rates. We need to balance granularity against number of multicast channels. If we had a video stream at OC-192 rates, would it make sense to have 3.75e+4 channels? Would the joins flood the NW? It would make sense to tune the channel rates to the expected use case. If 99% of the users have the same capacity, then we can be coarse. If the bell curve of capacity is low and wide, then we need to be more granular. The only way to find the optimal channel rates is through off line analysis, either using mathematical analysis (Bertsekas, Kleinrock, Jackson etc.) or a discrete event simulation (DES) such as Riverbed SteelCentrall NetPlanner. Off line analysis, however, requires user profiles, use cases and real life network metrics.

The following diagram illustrates a poor design choice. We have three channels, the base channel is set to T1, wave 1 is an OC-12 and wave 2 is an OC-192. A receiver with an OC-12 does not have enough capacity to join the base and wave 1, so he is stuck with just the T1 rate, a very poor efficiency.

The final issue for WEBRC deals with the length of periods for joins. We need to balance the join/leave times against available BW fluctuations. For example, if a receiver joins a channel and the BW drops significantly, the receiver can’t leave that channel until the next time slot (RFC3738 13). For the duration of the time slot, the traffic congestion may choke other congestion protocols (like TCP). The RFC recommends 10s/period (RFC3738 9). Since our data rate is constant, the receivers should not have any surprises, and this period duration should suffice. This however is still an issue and needs to be observed and addressed during live transmissions.

LCT Integration Issues

LCT provides a convenient mechanism for setting the mandatory transport session ID. As per the RFC, we have the option of using the 16-bit UDP port field to carry the TSI (RFC5651 9). I would recommend against this, since we cannot guarantee that downstream receivers would use some sort of port address translation or firewalling. Since the LCT header is mandatory and contains a field for the TSI, it’s best to just set the TSI there.

FCAST Integration Issues

To recap, FCAST uses sessions to send objects to receivers. FCAST sends objects by creating a carousel instance, filling the carousel instance with objects, and then using a carousel instance object to let receivers know which objects the carousel instance carries (RFC6968 8).

FCAST uses one session per sender, and in each session each object must have a unique Transport Object Identifier. Our integration engineers need to be aware of the potential for TOI wrapping, for long-lived sessions (RFC6968 10). FCAST gets the TOI from the LCT header.

The LCT RFC allows a finite number of bits in the LCT header for TOI (RFC5651 17). Thus, for long-lived sessions (days, weeks), TOI wrap and present ambiguity to receivers, similar to the issue of byte sequence number wrapping for TCP. A receiver may receive two separate objects with the same TOI in the course of a long-lived session. With “on demand" mode, carousels cycle through the same pieces of data a set number of times. Consider a large carousel instance, where FCAST sends an object with TOI “1”, followed by enough objects to wrap the TOI.

During the first cycle, the CI sends another, newer object with TOI “1.” The cycle finishes, and FCAST starts the cycle again, sending the original object with TOI “1.” The receiver has no idea what to do with the object of TOI "l," since it alternates as a reference for two distinct objects. A way to prevent this issue is, once FCAST reaches the halfway point of sequence numbers, it resends any old data with a new TOI. Another way to prevent TOI wrap ambiguity is to have metadata associated with TOI, so the receiver can distinguish between two objects with the same TOI. [RFC6968 10-11]

Another integration issue relates to the Carousel Instance Object (CIO). As mentioned in the above paragraph, the CIO carries the list of the compound objects that comprise a Carouse1 Instance, and specifies the respective Transmission Object Identifiers (TOI) for the objects. The CIO contains a "complete” flag that informs the receiver that the CI will not change in the future (i.e. FCAST guarantees the sender will not add, remove or modify any objects in the current carousel instance). Consider a receiver that receives a CIO with a "complete" flag. We may be tempted to use the list of Compound Object TOI as a means to filter incoming data. The issue, however, is that FCAST treats the CIO (list of objects) as any other object, that is, there are no reserved TOI that designate an object as a CIO. Thus, the receiver will never know in advance the TOI of CIO, so the RFC recommends that the receivers do not filter based on TOI. If a receiver were to filter out all but the TOI received in CIO with a “complete” flag, that receiver would also filter out any new CIO for new carousel instances associated with the session, and the receiver may miss out on interesting objects. [RFC6968 9]

FCAST, finally, allows integrators to send an empty CIO during idle times. The empty CIO lets RX know all previous objects have been removed, and can be used as a heartbeat mechanism. [RFC6968 9-10]

Conclusion

Real time video content delivery systems are a challenge due to the constant, high data rates involved. RT Video CDP lend themselves to circuit switched networks that can reserve enough bandwidth from sender to receiver and let the data fly. The next best architecture would be packet switched networks that were designed for multimedia, such as the Integrated Services Data Network (ISDN) or ATM. Our customer, unfortunately, required us to deploy a CDP on the Internet. To make matters worse, they required our CDP to handle millions of simultaneous receivers. Normally, when delivering constant rate video on the Internet, engineers will use a signaling technology such as resource reservation protocol (RSVP) to guarantee bandwidth from sender to receiver. An end to end (E2E) reservation scheme, however, does not lend itself well to a system with one sender and millions of receivers.

Our challenge, therefore, was to identify and deploy a one to many, massively scalable CDP that provides asynchronous, reliable and fair, multi-rate streaming data transport. We identified a solution based on IETF standards. This paper went through the solution intent, the technologies used, the integration choices made, the integration issues avoided and the validation steps performed to ensure the success.

Update: January 2019:

In the end, we successfully integrated the architecture and met all of Warner Brothers’ requirements. Averaged over the course of the movie, the average receiver ran at 90% of the available network capacity, and utilized 87% of processor resources. The bit error rate for the average receiver was 1e-13. Finally, both Anthony Michael Hall and Dwayne 'The Rock" Johnson went on to win academy awards for best actor and best supporting actor.

Bibliography

[RFC3453] Luby, M., Vicisano, L., Gemmell, J., Rizzo, L., Handley, H. and J. Crowcroft, “The Use of Forward Error Correction (FEC) in Reliable Multicast”, RFC 3453 December 2002.

[RFC3738] Luby, M. and V. Goyal, “Wave and Equation Based Rate Control (WEBRC) Building Block”, RFC 3738, April 2004.

[RFC5651] Luby, M., Watson, M. and L. Vicisano, “Layered Coding Transport (LCT) Building Block”, RFC 5651, October 2009.

[RFC5775] Luby, P., Watson, P. and L. Vicisano, “Asynchronous Layered Coding (ALC) Protocol Instantiation”, RFC 5775, April 2010.

[RFC6968] Roca, V. and B. Adamson, “FCAST: Scalable Object Delivery for the ALC and NORM Protocols”, RFC 6968, July 2013.