Yukio Mishima's Sea of Fertility tetralogy includes themes of reincarnation, futility, inevitably, and tradition. The novels follow the life of Shigekuni Honda and his peers in post-Meiji Japan. Even though Mishima's teens faced adolescence one hundred years ago, their experience resonates with teenagers today. Mishima's teens capture common realities of the human journey.

This blog post discusses how Mishima's teenage archetypes face the universal themes of general anxiety, social isolation, and life without purpose.

General Anxiety

Mishima's teens face general, amorphis and vague anxiety.

When Honda, in Spring Snow, contemplates the future of his one true friend Kiyoaki it drives him with:

a feeling of foreboding that he could not pin down (SS 93)

Later in his adult life, feelings of doom smother Honda. In Temple of Dawn, he feels:

simp[e] uneasiness... the same unsettled feeling, the precise category of emotion he experience[s] when he shave[s] himself badly or nights when he [can] not find a comfortable position for his head on the pillow (TD 162)

When they stand for ideals in Runaway Horses, life plunges:

Isao and his comrades... into a world of ever-growing uncertainty and anxiety, a world like the reflection of the moon adrift on a night sea (RH 286)

The entire city of Tokyo lives in fear. Mishima writes:

Something like an unseen gas seem[s] to have enveloped everything without anyone having noticed. People's eyes [get] moist. They [walk] as though in a dream. It seem[s] as though everyone wait[s] anxiously for some impending event (RH 239)

Social Isolation

In addition to general anxiety, teenagers fear social isolation. Mishima's teens want the boys to include them, his teens do not want the label of loner. Mizoguchi from The Temple of the Golden Pavilion says at the novel's opening that he:

[has] a weak constitution and [i]s always being defeated by the other boys in running or on the exercise bar... [and] has suffered since [his] birth from a stutter, and this [makes him] still more retiring in [his] manner (TGP 5).

He identifies the causes of his isolation and says:

My stuttering, I need hardly say, place[s] an obstacle between me and the outside world (TGP 5)

and:

The only points of difference [between the other students and I is] that I [am] a stutterer and a trifle uglier than the other students (TGP 35)

His friend Kashiwagi lends a hand and explains Mizoguchi's lack of success with girls. Kashiwagi says:

There's nothing beautiful about you at all. You have no success with girls and you don't have the courage to have professional girls (TGP 94)

Mizoguchi accepts the building isolation. He tells himself:

The most effortless existence for me [is] in fact one in which I [am] not obliged to speak to anyone (TGP 135)

and:

The fact of not being understood by others [is] my sole source of pride since my early youth, and I ha[ve] not the slightest impulse to express myself in such a way that I might be understood (TGP 135)

Mizoguchi's physical and verbal defects drive his misanthropy and social isolation.

Kiyoaki, the protagonist of Spring Snow, however, isolates himself from his peers on account of his overflowing pride. Emotions drive Kiyoaki. In describing him, Mishima writes:

The only thing that seems valid to him in his life is to live for emotions- gratuitous and unstable, dying only to quicken again, dwindling and flaring without direction or purpose (SS 15)

Mishima speculates on the source of Kiyoaki's sensitivity. He writes that his father Marquis Matsugae:

had sent the boy, still a very small child, to be brought up in the household of a court nobleman. Had he not done so, Kiyoaki would probably not have developed into so sensitive a young man (SS 5)

Kiyoaki's disdain for his peers drives him further into isolation. Mishima writes that the:

instinctive rejection of anyone who showed him affection, this need to react with cold disdain, [is] a failing of Kiyoaki's" (SS 21)

Kiyoaki dislikes anyone and almost everyone. In describing Kiyoaki's school, Mishima writes of:

an atmosphere of Spartan simplicity ...[and that] Kiyoaki, who had an aversion to anything smacking of militarism, had come to loathe [it] for this reason (SS 13)

Mishima furthers the point, and writes that:

Kiyoaki hated the idealistic cries that rose from those young throats... his classmates' rough-and-ready relationships, their untried humanism, their constant jokes and puns [and] their never faltering reverence for the talent of Rodin and the perfection of Cezanne (SS 170)

Kiyoaki's and Mizoguchi's early isolation echoes Mishima's. In his biography The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima author Henry Scott Stokes writes that Mishima's protective Grandmother suffocates and isolates him. His Grandmother raises Mishima (ne Kimitake):

as a little girl, not a boy. He [i]s always attended by a nursemaid, although this annoy[s] him greatly; he [is] not allowed to run about in the house, and he [is] forbidden to go out" (YM 56)

Stokes reveals how Mishima's grandmother shapes:

a dual personality... [One being] in retreat from life (YM 67)

Mishima in his youth:

stay[s] apart from his contemporaries; they ha[ve] little to offer him, for his precious intelligence put[s] him in a different class from them. And his parents, who, pleading his ill health, [insist] that he not spend the regulation two years boarding at the Gakushuin dormitory, encouraging his tendency to remain apart (YM 76)

Of his peers, Mishima writes they:

do nothing but always think immoderately about women, exude pimples, and write sugary verses out of heads that were in a constant dizzy reel (YM 78)

Stokes calls Mishima's withdrawal from his contemporaries:

his own little castle... his dark cave (YM 97)

Mishima exhibits duality and intersperses apathy for his peers with awe. He worships them for the qualities he lacks. He:

worship[s] all those possessors of sheer animal flesh unspoiled by intellect-- young toughs, sailors, soldiers, fishermen— but [is] doomed to watch them from afar with impassioned indifference (YM 71)

Except for an occasional literary club (Bungei-Bu), isolation defines Mishima's formative years.

Life Without Purpose

Teenagers experience another feeling worse than the fear of death or the pain of social isolation, a feeling of life without purpose. Disenchantment and meaninglessness drive this feeling.

Mishima conveys this feeling through his Teenagers. Mizoguchi, for example, in The Temple of the Golden Pavilion says:

in the darkness of the dawn, in the black trees, in the black summits of the Aobayama, yes, even in Uiko who now stood before me, there [i]s a complete and terrible meaninglessness (TGP 11)

Mishima's character Isao, from Runaway Horses, expresses the meaninglessness of human life via biological jargon. He reduces life to a:

futile, laborious process in which ontogeny [is] eternally recapitulating phylogeny, in which a man forever trie[s] to draw a bit closer to truth only to be frustrated by death, a process that ha[s] ever to begin again in the sleep with amniotic fluid (RH 337)

In the next novel of the Sea of Fertility tetralogy, The Temple Of Dawn Mishima minimizes the "meaning" of life. He writes:

From the standpoint of fate, living [i]s like being swindled. And human existence... signifie[s] nothing but the lack of fulfillment (TD 210)

In the last work in Mishima's tetralogy, The Decay of the Angel, Mishima conveys through the central character Toru that:

We are too accustomed to the absurdity of existence. The loss of a universe is not worth taking seriously (DA 6)

He imparts a final sense of insignificance at the finale of the novel. Honda talks with Satoko, the Abbess of Gessuhuji, and debates if Kiyoaki existed.

Honda says:

If there was no Kiyoaki, then there was no Isao. There was no Ying Chan, and who knows, perhaps there has been no I (DA 235)

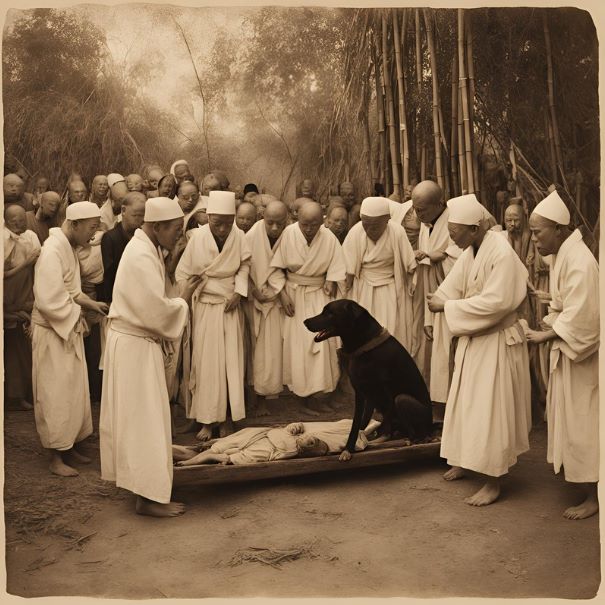

The Temple of the Dawn opens with a macabre Bombay scene that commoditizes death:

Just then another white-swathed corpse arrived, borne on a bamboo litter and surrounded by chanting priests and all the relatives. Several children and a black dog chased each other around the feet (TD 65)

Mishima captures the brief absurdity of human existence. He hints at the meaninglessness of life and attributes little importance to that meaninglessness. The narrator captures Honda's resignation to this lack of importance and says:

He has simply become the captive of the egoistic and melancholy conviction that henceforth his life would definitely end and he would never achieve greatness. But had he ever really desired that in life? (TD 101).

Toru, in The Decay of the Angel furthers this theme, when he writes the following in his diary:

It is at such times that I [Toru] see myself with wings that have no obstacles, and I see to that I shall do nothing at all with my life (DA 156)

Mishima's characters appear at least superficially to have accepted the meaninglessness of human life, and their unimportant lots in it.

Reincarnation

The theme of reincarnation flows through the Sea of Fertility tetralogy. Mishima devotes a major portion of The Temple of Dawn to a quasi-textbook-like discussion of its history and proliferates discussion of the topic throughout the cycle.

Stokes attributes Mishima's Reincarnation fixation to overcompensation. He postulates that Mishima wants to convince the reader that he believes in reincarnation.

Stokes writes that Mishima:

was not a religious man and his description of Hosso's teaching reads like part of a doctoral thesis... Here was a major problem for the writer: how to make an idea convincing when he did not believe it himself (YM 149)

Stokes also adds that Mishima "was afraid that the Buddhist" theme running through his long novel-- the idea of reincarnation --would fail. Specifically, Mishima thought that if the reader did not believe he was serious about reincarnation then he would regard the entire novel "as a kind of fairy story" (YM 165).

Next month continues the discussion of Mishima's Teenage Archetypes.

Bibliography

- Mishima, Yukio. The Decay of the Angel. Trans. Edward G. Seidensticker. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

- ---. Runaway Horses. Trans. Michael Gallagher. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

- ---. The Sailor Who Fell from Grace With the Sea. Trans. John Nathan. New York: Alfred A./t Knopf, 1965

- ---. Spring Snow. Trans. Michael Gallagher. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

- ---. The Temple Of Dawn. Trans. E. Dale Saunders and Cecilia Segawa Seigle. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

- ---. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Trans. Ivan Morris. New York: Vintage International, 1994

- Stokes, Henry Scott. The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1975