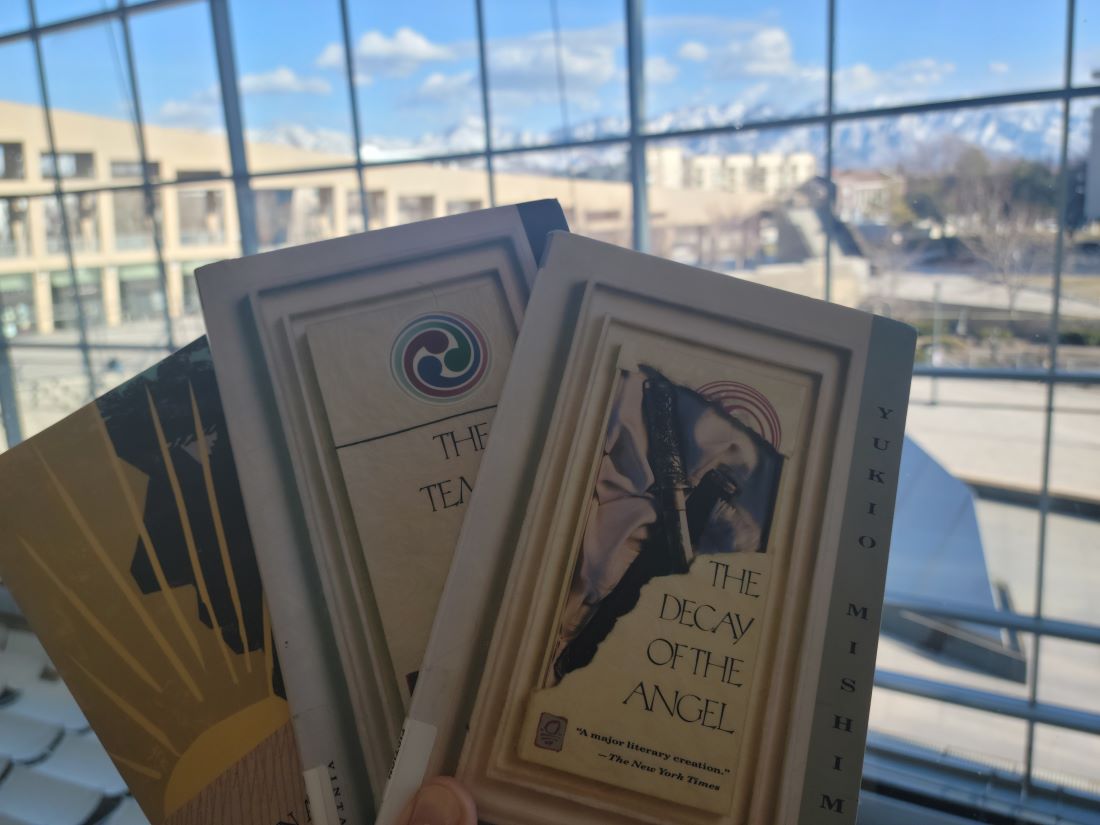

Our bipartite Literary analysis of Yukio Mishima's Sea of Fertility tetralogy concludes this month. We further illustrate how Mishima's post-Meiji Japan teens capture timeless realities of the human journey.

Last month, we discussed how his teenage archetypes face general anxiety, social isolation, and life without purpose. This month we discuss the collective experiences of search for Identity and injurious Father/Son relationships, experiences which complete the mythos of the teenage Archetype.

The Search for an Identity

To transition to adults, adolescents must accept their place in the world and history. Unlike children, adolescents begin to understand their ability, status, and therefore fate. Adolescents can make peace and accept their fate, refuse to accept their fate, or do neither and complain.

Honda praises the virtue of the first method, yet like most philosophers constantly debates throughout the tetralogy whether or not he should live in such a manner. Regardless, Honda says:

...there's only one way to participate in history, and that's to have no will at all— to function solely as a shining, beautiful atom, eternal and unchanging. No one should look for any other meaning in human existence (SS 101)

He reiterates this notion practically verbatim in the next book in the tetralogy:

... vehemently maintaining that every strong-willed person [is] in the last analysis frustrated and that there [is] only one way to participate in history: ‘To function as a shining, forever unchanging, beautiful non-willing particle' (RH 213)

In describing Honda, Mishima writes that he:

...can not avoid misgivings as to the ability of [his] will to change anything or to accomplish anything even in contemporary society, let alone the course of human history (RH 214).

Stokes writes that Mishima follows the edict of Dostoyevsky, who wrote:

...the basic proposition of the modern novel is ... the expression of opposed attitudes within human beings (YM 115)

Mishima contrasts Honda's resignation with Isao's belligerence. Isao fights society and does not blindly accept his assigned role. Isao and his friends swear loyalty to a militant cause. Mishima ponders the motivation, and speculates that the youths fight for glory vs. any ideal:

Each and every [youth in Isao's Militia] is eager to embrace a cause that he could brag about to others and [is] hoping for the most exquisite of funeral wreaths to mark his passing (RH 196)

Isao devotes his life to a single cause: a beautiful, honorable suicide preceded by political assassinations which:

...would, beyond any doubt, send a severe shock through the economic structure of the nation (RH 292)

Motivation aside, Isao and his comrades remain steadfast in their ideals. He explains to the cops after his arrest:

If we made them a little more flexible, it wouldn't be the same. That little[emphasis mine] is the point. Purity can't be toned down a little. If you make it a bit flexible, just a bit, it becomes a different idea, not the kind we hold... (RH 352)

The reader suspects that suicide drives Isao's political crusade. He holds a romantic view of suicide and treats it with impatience. He lies to expedite the execution of his suicidal plan, and rationalizes the lie:

Isao did not think of himself as lying. If something was not designated by the gods as either true or false, then it would be highly presumptive for a human being rashly to think of it as a lie (RH 262)

Isao's suicide fantasy consumes his life:

Nevertheless, Isao would not give up his dream: somewhere a place awaited him where all the elements of seppuku came together... the vision of dying on a mountain peak, as the sky gradually lightens to reveal trailing clouds and white pendants fluttering in the morning breeze (RH 266).

Isao believes only his suicidal political mission will bring meaning to life. Honda reflects in The Temple of Dawn:

...the will to engage oneself in history is the essence of human purpose (TD 21)

In Runaway Horses, Mishima imparts upon us that:

The concept of suicide remained for Isao what it had always been, something extraordinarily bright and luxurious (RH 334)

Henry Scott Stokes argues in his biography that Mishima shares analogous feelings with Isao regarding suicide. He writes:

Suicide, it is clear from Mishima's writing, has been a theoretical option for him for many years (YM 141)

Mishima's infatuation with suicide over the years transcends media, including film, in which he:

...play[s] the part of an army lieutenant who commits hara-kiri (YM 145)

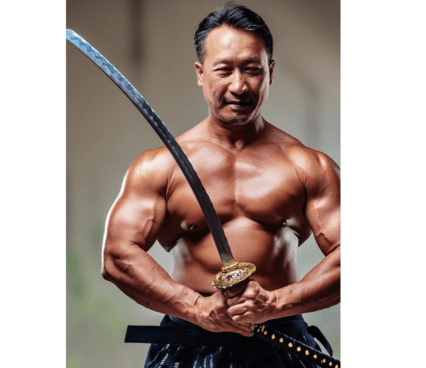

and photography- where

...amongst the poses which Mishima strikes] for [an] unpublished volume [of photographs a]re a number in which he committ[s] Hara-kiri (YM 192)

Instead of accepting the grim reality of Suicide, Mishima appraises the act through a novel, romantic, and childlike lens.

Before Mishima, Japanese authors avoid the topic of Suicide. Stokes writes:

...no other Japanese novelist of repute has ever written (of Suicide) (YM 160)

At certain times, Mishima treats suicide with the frivolous delirium of a twelve-year-old girl talking about her first crush. When Mishima forms his Tatenokai and inevitably kills himself for political commentary, one suspects that his crusade provides a vehicle for his suicide. You can argue the same for Isao.

Insight into Isao's drive to Hari-kari illuminates Mishima's impetus.

Stokes repeats in Mishima's biography that experts still debate Mishima's true motivation. Mishima may desire to clutch in his hands and drink from the same Holy Grail that decants purpose to his fated protagonist from Runaway Horses. Perhaps a sip from that Holy Grail rectifies his lies to the Army doctor who performed his physical (YM 92), or possibly it gives him some barbaric sexual thrill (YM 249), we do not know.

Mishima, nonetheless, considers suicide the one ideal that will complete his life and give it meaning.

Part 3: The Effects of an Injurious Father/ Son Relationship

In addition to inexplicable doom sensations, feelings of hermetic isolation from rough and mean peers, and the nagging starvation for that one nourishing ideal or object that will make life worthwhile, some teenagers and young adults face the harsh reality of having poor relationships with their Fathers.

Poor relationships include heated disagreements, clashes of ideals, or, in extreme cases, an Oedipal complex.

While modern psychologists dismiss Freud's Oedipal Complex hypothesis, we nonetheless find examples in both Literature and Life. Mishima himself suffers from this Freudian malady. In The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, Stokes writes:

When Mishima started to live with his mother he fell in love with the poor, beautiful woman who had been treated so cruelly by her awful mother-in-law. As they had been separated for such a long time the reunion between mother and son was scarcely normal. Mishima was a most sensitive age, the start of his adolescence. Later in life, [his mom] would refer to her son as 'lover'... she hid her actions from her husband, as Azusa wanted his sons to follow the family tradition of government service and thoroughly disapproved of literature as a career for the boy (YM 68)

Mishima's The Sailor Who Fell from Grace With the Sea includes the scenario of an Oedipal complex.

An unnatural infatuation with his Mother hounds Noboru, the central character in The Sailor Who Fell from Grace With The Sea. He spies on her on every occasion through a peephole in his dresser:

The night [is] humid, the space inside the chest so stuffy he can barely breathe: he crouche[s] just outside, ready to steal into position when the time c[omes], and wait[s] (FFG 10)

Mishima writes how Noboru "trembles" when he spies on his mother and how he had never "observed a woman's body so closely" (FFG 7).

The narrator also says:

... on moonlit nights [Noboru's] mother would turn out the lights and stand naked in front of the mirror... (FFG 8)

which would cause Noboru to

..lie awake for hours, fretted by visions of emptiness (FFG 8)

Norubu resents his deceased Father and all Fathers, which strengthens an Oedipal interpretation of Fell from Grace. Mishima writes:

...fathers and teachers, by virtue of being fathers and teachers, [are] guilty of a grievous sin. Therefore, [Noboru's] own father's death, when he was eight, had been a happy incident, something to be proud of (FFG 8)

The Sailor Ryuji replaces Norubu's Father, and Norubu resents Ryuji. Noboru creates a diary that lists the infractions his mother's new companion commits against Norubu and Norubu's principles. Mishima writes:

...red with rage and coughing violently, Noboru pulled his diary from under the pillow as soon as [his mother and Ryuji] had left, and wrote a short entry:

Charges against Ryuji Tsukazaki (FFG 105)

Ryuji eventually marries Norubu's mother. With an official second Father, Norubu increases his hatred for Ryuji. He shares his friend Chief's sentiment regarding Fathers:

Fathers! Just think about it for a minute-- they're enough to make you puke. Fathers are evil itself, laden with everything ugly in man... There is no such thing as a good father because the role itself is bad. Strict fathers, soft fathers, nice moderate fathers-- one's as bad as another. They stand in the way of our progress while they try to burden us with their inferiority complexes, and their unrealized aspirations, and their resentments, and their ideals, and the weaknesses they've never told anyone about, and their sins, and their sweeter-than-honey dreams, and the maxims they've never had the courage to live by-- they'd like to unload all that silly crap on us, all of it! Even the most neglectful fathers, like mine, are no different. Their consciences hurt them because they've never paid any attention to their children and they want the kids to understand just how bad the pain is-- to sympathize! (FFG 136-37)

After the engagement, Noboru still spies on his mother, although:

...the danger in sneaking into the wall in broad daylight, with the door not even locked, discouraged him from risking the adventure again (FFG 148)

Noboru, however, decides to spy once more, and this time he gets caught. He incurs the wrath of his mother and pseudo-discipline from Ryuji.

Ryuji's soft, rational, almost affectionate "punishment" makes Noboru hate the man even more for it. Noboru laments:

...the sailor [is] saying things he never meant to say. Ignoble things in wheedling, honeyed tones...words such as men mutter in stinking lairs. And he [is] speaking proudly, for he believe[s] in himself, [is] satisfied with the role of the father he had stepped forward to accept (FFG 158)

His hatred for his father compels Noboru to lure Ryuji to the docks, where his psychopathic friends wait. [Spoiler] They murder him and dissect his corpse.

In The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea, Noboru fulfills half of the Oedipus Story. Mishima concludes the theme of the Son/ Father conflict with Patricide.

Runaway Horses also addresses Father/ Son conflict in greater depth than Fell from Grace. In Runaway Horses Isao's father, unlike Noboru's in Fell from Grace, recognizes the injuries he inflicts on his son. He understands the ramifications of his actions, wrestles with his guilt, and weighs the importance of his needs against his Son's.

When he considers turning Isao in to the Police he says:

I wanted to save your life and I wanted to see your plan through. But what should I do? (RH 404)

Mishima emphasizes that a lack of communication creates rifts between Father and Son. Iinuma bars Isao from seeing Prince Toin with no explanation. Mishima explains Iinuma's conduct:

The truth of the matter [i]s that Iinuma, as Isao's father, should have been able to explain his repugnance for the Prince so that his son could have readily understood it... Shame however, like a rock glowing red with heat, blocked Iinuma's throat and prevented all explanation (RH 179)

Mishima writes:

For the first time Iinuma realized that there [i]s an inviolable core within his son, and now he, who had failed in attempting to form Kiyoaki, in another time and in quite different circumstances, felt the same enervating frustration with Isao and could not stem a sudden rush of anguish (RH 179)

In Runaway Horses, Mishima shows the Father's perspective.

Conclusion

Between childhood and adulthood lies the teenage years. Regardless of Epoch, Teenagers experience universal pain. Yukio Mishima's Sea of Fertility tetralogy captures the universal struggles that all Teenagers face.

We close with a quote from Spring Snow that best illustrates the teenage condition.

Kiyoaki, the lovelorn, over-emotional protagonist of the work laments:

I've been left all alone. I'm burning with desire. I hate what's happening to me. I'm lost and I don't know where I'm going. What my heart wants it can't have... my little private joys, rationalizations, self-deceptions-- all gone! All I have left is a flame of longing for times gone by, for what I've lost. Growing old for nothing. I'm left with a terrible emptiness. What can life offer me but bitterness? Alone in my room... alone all through the nights., cut off from the world and from everyone in my own despair. And if I cry out, who is there to hear me? (SS 356)

Bibliography

-

Mishima, Yukio. The Decay of the Angel. Trans. Edward G. Seidensticker. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

-

---. Runaway Horses. Trans. Michael Gallagher. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

-

---. The Sailor Who Fell from Grace With the Sea. Trans. John Nathan. New York: Alfred A./t Knopf, 1965

-

---. Spring Snow. Trans. Michael Gallagher. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

-

---. The Temple Of Dawn. Trans. E. Dale Saunders and Cecilia Segawa Seigle. New York: Vintage International, 1990.

-

---. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion. Trans. Ivan Morris. New York: Vintage International, 1994

-

Stokes, Henry Scott. The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., 1975