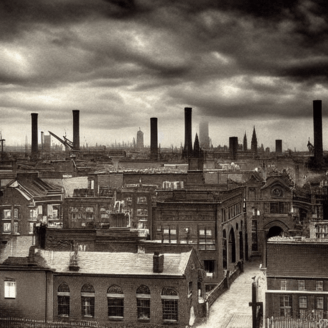

Hopkins refers to a “year” of “done darkness.” 1885 marks this year, the year Hopkins wrote “[Carrion Comfort].” For Hopkins, 1885 includes “encroaching derangement” that consumes him (Harris 12).

Harris calls Hopkins’ situation “a recurrence of the melancholia” he experiences in 1866 (12). Harris says how Hopkins uses the prose “fits of sadness” which “resemble madness” to refer to “melancholia” (12). The year in which Hopkins “lay wrestling” with God, therefore, marks madness, a madness of depression induced by the City (14).

Click Here to read Part 1 or here to read Part 2

I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark, Not Day

Hopkins also deals with City-induced madness and depression in his “I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark, Not Day.”

Akin to the other “Terrible Sonnets," the presence of depression and madness in the poem reflects not an absence of faith within Hopkins, but rather an absence of God’s presence within Hopkins’ world. Ellis writes, “the evidence of this sonnet... testifies mainly not to the priest’s abandonment of faith but to the poet-priest’s attempt to shape into art and insight a great darkness, a darkness that was most terrible because it issued from great faith” (280). The poem casts Hopkins into a seemingly eternal night of misery, combining “thwarted hope of reprieve with doomed acceptance of continued disaster” (Harris 77).

The metaphorical night represents a period of depression that Hopkins experiences. The internal poem unravels in Hopkins’ mind, from a place with no connection to God. Instead of any Divine presence, there exists only chaos in Hopkins’ mind. He finds no reality “but the self, the inner mind and the foul body in which that mind is locked, and the unimaginably remote cosmic spaces, where perhaps a departed God ‘lives alas! away’” (Ellis 281). The first quatrain of the poem relates the endless nature of the metaphorical night:

1 I wake and feel the fell of dark, not day.

2 What hours, O what black hours we have spent

3 This night! what sights you, heart, saw; ways you went!

4 And more must, in yet longer light’s delay.

Lines two and three tease us. The past tense of these two lines insinuates the night's end, with the poet free from the turmoil of the night’s machinations. Unfortunately, line four reveals more to come. The quatrain, therefore, shows the inarticulate and obfuscate nature of the rules of the night. The absence of a definitive end to the night gives the reader “the nightmarish sense that time is wholly disjointed, that it is both terribly present and terribly endless” (Ellis 282).

The verb “saw” in line three conveys that, despite the darkness, Hopkins sees the “sights” of night. He sees and registers all of the atrocities of the night that give him pain. Ellis writes, “darkness does not bring blessed blindness...the heart must instead ‘see’ only too clearly the horrors besetting its dark journeyings [sic]” (283).

Hopkins uses “fell” in both the title and the first line of the poem. “Fell” to the common reader elicits notions of felled trees. With this definition, we read that God fells darkness (like a tree), and the weight falls on Hopkins. MacKenzie, however, points out that those classically educated in the manner of Hopkins recognize “fell” to define a type of “skin or hide (from the Greek word pellis)” (MacKenzie 181).

The “fell,” or hide, of dark anthropomorphizes it into a feral beast of some sort (1). Ellis writes, the word fell “convey[s] the crushing weight and terrifyingly tactile presence of this huge and shaggy beast of darkness, a creature that is clearly not the lion-limbed savior of ‘[Carrion Comfort]’ and may be in part the poet’s own dark physicality” (282).

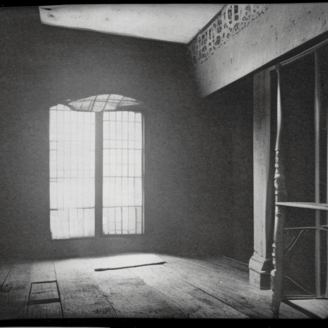

Ellis reminds us of one nightmare in which a feral beast pounces upon and pins Hopkins. This attack incites Hopkins to think that the Devil imprisons souls in hell in a like manner. Hopkins writes: “I had a nightmare [one] night. I thought something or someone leapt onto me and held me quite fast... It made me think that this was how the souls in hell would be imprisoned in their bodies as in prisons” (Ellis 282). Therefore, the bestial nature of Hopkins’ night imprisons him in the same pinning manner that the Devil imprisons “souls of hell.”

Imprisonment results from sentencing, and sentencing results from a court procession. Hopkins carries this law imagery through the second stanza:

5 With witness I speak this. But where I say

6 Hours I mean years, mean life. And my lament

7 Is cries countless, cries like dead letters sent

8 To dearest him that lives alas! away.

The statement “But where I say / Hours I mean years, mean life” (5-6) further strengthens the inconclusive, seemingly eternal nature of the night. On this night, with no end in sight, Hopkins detaches from God, who “lives alas! away,” and never receives Hopkins' “countless” cries, making them akin to “dead letters” (7-8). Notice, however, “that the second quatrain does not state that for Hopkins God is dead. On the contrary, he specifically implies that He lives (8)— but unreachably somewhere else” (MacKenzie 182).

Nonetheless, the “dead letters” simile may seem rather amateurish for the accomplished poet Hopkins. But Ellis writes, “a more elevated simile could not make us feel and recognize the sense conveyed here of deep personal injury and loss, the loss of a once dear and intimate friend who has now moved on, without a word, without caring” (284). In addition, much of Hopkins’ dialog with God uses the written word (284). “Letters” compose Hopkins’ sonnets, sermons, and journal entries.

In the Sextet, Hopkins analyzes the physicality of his prison, and compares it to those in hell:

9 I am gall, I am heartburn. God’s most deep decree

10 Bitter would have me taste: my taste was me;

11 Bones built in me, flesh filled, blood brimmed the curse.12 Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours. I see

13 The lost are like this, and their scourge to be

14 As I am mine, their sweating selves; but worse.

Hopkins tastes his own physicality, he dines on his “flesh” and “blood” and “sour dough” of spirit in a perversion of the Eucharist (Ellis 286). Digestion or rather indigestion produces “Gall” and “Heartburn.” His autocannibalism (flesh-eating) sickens him, which symbolizes an act of sin. Hopkins says that God decrees him to a predisposition for sin because God creates his “fleshy vessel of sin” in the first place (Ellis 286). Hopkins builds the mental prison to punish his sin.

Ellis says the last two lines faintly echo one of Hopkins’ earlier prayers: “O Jesus, O alas Jesus Christ our Lord, we are sinners, spare us; they died impenitent, they lie in hell, we are on earth, there is time yet, we are sorry for our sins, we do repent, thou spare us” (287). Hopkins compares his situation to that of “the lost,” but admits he has a better situation since he can still repent. These lines provide “evidence of Hopkins' spiritual honesty and discipline” (Ellis 288). MacKenzie reminds us of the inconclusive ending. He says that “the fell of dark remains in this poem unalleviated” (184).

This poem captures a depressed, isolated Priest unable to reach communication with God. He cannot reach God on account of his self-imposed prison. Hopkins constructs a prison to punish himself for failings he has acquired on account of the City’s influence. His confinement then leads to “the fell of dark,” or depression.

To Seem the Stranger

“To Seem the Stranger” also represents depression. “To Seem the Stranger” reads less obfuscate than the other “Terrible Sonnets.” “No Worst, There is None” and “I wait and feel the fell of dark, not day” deliver enigmas that the reader addresses through vigorous explication and a thorough understanding of Hopkins’ life history. “To Seem the Stranger,” however, nearly states outright the causes for the pain it depicts. Concrete, tangible incidents cause Hopkins’ pain in “To Seem the Stranger.”

Hopkins opens with the first reason for his pain:

1 To seem the stranger lies my lot, my life

2 Among strangers. Father and mother dear,

3 Brothers and sisters are in Christ not near

4 and he my peace/ my parting, sword and strife.

The first line, “To seem the stranger lies my lot” reflects Hopkins’ feelings of ostracism. Hopkins, an Englishman, lives in an Irish city and belongs to a predominantly Irish religion, Catholicism. The rest of the stanza indicates the pain he feels from the “removal from his family by their differences in religion” (Martin 384).

His conversion to Catholicism, “though it brought his mind peace, parted him in sympathy from his own family, who were Anglicans” (MacKenzie 179). For the first two stanzas, Hopkins “laments, first, his separation from his family in matters of religion, and secondly, his physical separation from England” (Bergonzi 134):

5 England, whose honour O all my heart woos, wife

6 To my creating thought, would neither hear

7 Me, were I pleading, plead nor do I: I wear-

8 y of idle a being but by where wars are rife.

The second stanza deals with the collective “Englishman's misunderstanding of him as a Catholic” (Martin 384). Their disapproval of his conversion inflicts pain on Hopkins. His extension of “weary” over two lines demonstrates this pain and “reflects an exhaustion that can barely drag itself from one word to the next” (Ellis 276). Martin points out this “is in part a poem about human relations as well as Divine,” noticing the glaring insertion of the word “wife” by Hopkins in line 5 (385).

The lack of positive “human relations” in his life brings Hopkins pain. Harris writes that “To Seem the Stranger’s” depiction of Hopkins’ failure with loving Mankind indicates his personally diagnosed failure to live up to his potential in Christ’s eyes. Harris says “the separation between the priest and his community that the ‘Terrible Sonnets' mirrors is the earthly correlative, within the process of daily religious life, of Hopkins’s inability to sustain his communication with Christ” (129).

Mackenzie, however, writes that readers “almost invariably misread” Hopkins’ pain regarding England (179). The word “wife” insinuates that Hopkins feels strong, matrimonial ties to England, and therefore must protect her name and honor:

9 I am in Ireland now; now I am at a third

10 Remove. Not but in all removes I can

11 Kind love both give and get. Only what word12 Wisest my heart breeds dark heaven’s baffling ban

13 Bars or hell’s spell thwarts. This to hoard unheard,

14 Heard unheeded, leaves me a lonely began.

MacKenzie writes that Hopkins “considered that a great work of art by an Englishman was ‘like a great battle won by England’, being praised even by those who hated her; but to achieve this action in her honor a work must become widely known (Letters, p.231)” (179). Hopkins’ works, however, during his period in Ireland, intended “to help England recover her spiritual honor by returning to the true Faith” (179) “issued in nothing but fragments” (Ellis 277). Mackenzie says, therefore, that Hopkins fails in “entering the battle for England’s honor by producing stimulating works which would redound to the national credit” (179). He says “others were busy fighting, while [Hopkins] was perforce idle, a mere bystander (11. 7-8)” (180).

Hopkins, “idle a being but by where wars are rife” states “his impotence not only as teacher-lover of humanity but as a soldier” (Ellis 276). Instead of being an active member in the crusade to bring England, and furthermore, Catholicism, honor, he finds himself “a mere sidelined soldier, an observer ‘but by’ (only on the periphery of) the war... in which he should but cannot be engaged” (276). Furthermore, Hopkins’ choice of the word “idle” imparts a “bare existence, without energy or purpose or choice... the futile and tedious continuation of something that ought to be life and action but is endlessly thwarted and inactive” (276). Hopkins writes this sonnet in response to his sense of failure at not producing any works of worth in Ireland. He blames this lack of muse on the city itself.

Patience, hard thing!

“Patience, hard thing!” also depicts a cowardly spectator (Hopkins), rather than an active soldier, in the war for God:

1 Patience, hard thing! the hard thing but to pray,

2 But bid for, patience is! Patience who asks

3 Wants war, wants wounds; weary his times, his tasks;

4 To do without, take tosses, and obey.

We translate lines 2-3 into conventional English: “he that asks for patience would rather see battle and receive wounds because he wearily spends his time on mundane and inconsequential tasks.” Taken further, the lines say: “only those engaged in mundane and inconsequential tasks would ask for patience, those engaged in worthwhile battle would never ask for patience.” MacKenzie writes, “the quality of patience is never required where there is excitement. No one engaged in active warfare ever needs it... but only those whose lives and whose jobs are dull” (184). Ellis agrees with such a sentiment, saying that Hopkins “initially view[s] [patience] as a thoroughly negative virtue” in he associates patience only with those avoiding their “soldierly” duties (289).

The act of asking for patience troubles Hopkins in this first stanza because he fancies himself a would-be hero, and by asking for patience, he counters that illusion. Ellis writes “it is difficult for Hopkins even to bring himself to pray for patience, because such a prayer is in itself an acknowledgement of his failure as a soldier of God” (Ellis 289). Hopkins carries the idea of equating the action of asking for patience with the action of deeming oneself a failure in the second stanza of the poem:

5 Rare patience roots in these, and, these away,

6 Nowhere. Natural heart’s-ivy Patience masks

7 Our ruins of wrecked past purpose. These she basks

8 Purple eyes and seas of liquid leaves all day.

In this stanza, “fastening and twining itself on ruin not only as a kindly mask but also as a somewhat parasitic growth, patience is still the virtue of the failed soul, and perhaps merely a mad king’s crown of wild weeds” (Ellis 291). Pride also prevents Hopkins from asking for patience. He dislikes the ask in that it reminds him of his own futility.

Patience should comfort the asker. St. Ignatius writes: ‘“Let him who is in desolation strive to remain in patience, a virtue contrary to the troubles which harass him; and let him think that he will shortly be consoled’ (‘Rules for the Discernment of Spirits’, viii, Father Morris’s edn, 1887)” (MacKenzie 185). Patience plays a positive role in the life of the sufferer. The language and word choice of the second stanza hides this positive role. Ellis writes:

On the other hand, seemingly almost against his will, the speaker simultaneously recognizes both the fertility of its soil and the softly natural, effortlessly beneficial quality of the virtue itself: “roots” and especially “natural heart’s-ivy” make it something neither hard in itself nor hard for the understanding heart to pray for, and in the lovely culminating image it has completely submerged all ruin, rock and hardness in a soft liquid shining (291)

Hopkins atones and humbles himself in the presence of God at the end of the sonnet:

9 We hear our hearts grate on themselves: it kills

10 To bruise them dearer. Yet the rebellious wills

11 Of us we do bid God bend to him even so.12 And where is he who more and more distills

13 Delicious kindness?—He is patient. Patience fills

14 His crisp combs, and that comes those ways we know.

Counter to the first stanza, he now “not only asks but in a sense humbly orders God to master his will— ‘Yet the rebellious wills / Of us we do bid God bend to him even so’ —and is willing to undergo the death-to-life that patience seems to involve and demand” (Ellis 293).

The sonnet, however, still ends unresolved. The question Hopkins asks in lines 9-10 “where is he who more and more distills / Delicious kindness?” remains unanswered.

In addition, Ellis points out that the poem ends with Hopkins knowing but not doing what he should do. He says, “to know is not necessarily to do, and that the attempt to do may lead to an endless circularity of search and suffering” (295).

Hopkins’ fear of admitting his failure incites pride and condemns him to a potentially “endless circularity of search and suffering” in the quest for peace. He turns his fear into anger and attacks the virtue of patience. He becomes defensive and irrational and refuses to accept the obvious. When he finally realizes his irrational pride, he identifies a course to ameliorate his situation. Fear causes his pride. Hopkins wears an inflated, false pride to shield himself from emotional pain. He does not feel pride from superiority over any other human being or divine being. He wears the pride of a panicked individual, sprung irrationally to postpone the inevitable acceptance of a painful truth.

My own Heart let me more have pity on

“Patience, hard thing!” ends with Hopkins knowing how to improve his life. In “My own Heart let me more have pity on,” Hopkins acts on this knowledge.

Unlike the other Terrible Sonnets, Hopkins attempts to break free of his psychological ruminations in this one:

1 My own heart let me more have pity on; let

2 Me live to my sad self hereafter kind,

3 Charitable; not live this tormented mind

4 With this tormented mind tormenting yet.

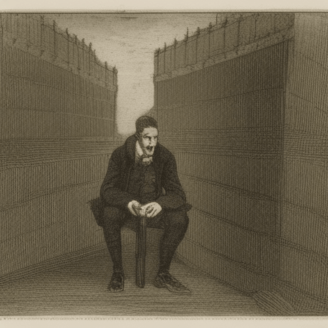

Hopkins does not win or lose the struggle in the first stanza, he rather “endure[s]” (Bergonzi 133). Hopkins’ “will to break out of the mind’s prison is not yet sufficient to unlock its doors” (Ellis 296). Instead, the “torture-chamber of the mind” traps Hopkins (MacKenzie 187).

The next quatrain includes prison imagery:

5 cast for comfort I can no more get

6 By groping round my comfortless, than blind

7 Eyes in their dark can day or thirst can find

8 Thirst’s all-in-all in all a world of wet.

Hopkins sits in a “prison cell devoid of light and furnishings..., a dissociation room designed to bereave a man of all his own resources” (187). The quatrain gives a “bewildered sense of futility, sense of exile, sense of reduction to animalism” (Ellis 297). He can do nothing more than “grope” around for comfort, like a scavenger hunting for carrion.

After this “claustrophobic image,” Hopkins finds himself in a Coleridgesque situation, dying of thirst, “surrounded by a hostile waste of undrinkable water” (MacKenzie 187). In the final sextet, however, he realizes the antidote to his situation:

9 Soul, self; come, poor Jackself, I do advise

10 You, jaded, let be; call off thoughts awhile

11 Elsewhere; leave comfort root-room; let joy size12 At God knows when to God knows what; whose smile

13 ‘s not wrung, see you; unforeseen times rather— as skies

14 Betweenpie mountains— lights a lovely mile.

He calls off thoughts and gives up the hunt for the answers to cure his desolation. Hopkins finds himself an “animal hunter who can only regain his humanity by choosing... not to hunt” (Elks 298). Elks writes:

Full humanity will only be restored to that Jackself when it ceases to be the blind plodder on the treadmill, the blind hound in darkness, when it becomes instead the master huntsman who chooses not to hunt, or at least to call off the hounds of thought from their present futile trail and to set them to some more promising scent outside the walls of self (299)

God “whose smile / ‘s not wrung” alone controls Hopkins’ life and fate. God acts “the ’wringer’” in all things, and never “the ‘rung...’” (300). Hopkins’ may not get a permanent change, because God lights only one “lovely mile” and not the entire Journey of Hopkins’ future life (301).

Regardless, this sonnet shows an attempt on Hopkins’ part to rid himself of demons.

Conclusion

While “My Own Heart” ends on a positive note, the speaker of the “Terrible Sonnets” never finds a resolution. Literary analysts do not know conclusively that Hopkins intended “My own Heart” to end the “Terrible Sonnets.” Literary circles agree that Hopkins did not intend the “Terrible Sonnets” to follow a particular order, and discourage any attempts to do so. Harris writes that we must read the poems “not as a developmental sequence but as a group whose unity [is] derived primarily from a common emotive pressure” (Harris 10). Hopkins' depression applies the “emotive pressure.” Hopkins' feeling of inadequacy, brought upon by the squalor and suffocation of the city, drives his depression.

Hopkins' earlier works lack deep philosophical rumination. “Pied Beauty,” “God’s Grandeur” and “Spring” demonstrate unquestioning obedience and wide-eyed awe at the splendor of God. The “Terrible Sonnets,” however, witness a dramatic departure from this paradigm, and deal with the pain of self-reflection. Hopkins questions his maker in the ‘Terrible Sonnets,” a contrast to his earlier unconditional acceptance.

We must not compare Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Terrible Sonnets” to The Book of Job. God punishes Job because of his pride. Job's pride stems from the belief that he could know the unknowable ways of God. God, however, does not punish Hopkins. Hopkins punishes himself. His punishment stems not from his pride, but rather from his piety. He strives for soldierly duty in God’s eyes, and when he feels wanting in his duties, he becomes depressed and miserable. His eagerness for piousness produces an overly sensitive reaction to failings that most of us would not dwell over. Hopkins' perception of failure causes pain, and this pain drives the “Terrible Sonnets.” He does not lack faith in God. We owe it to Hopkins, therefore, to recognize that Hopkins wrote these sonnets of desolation not on account of “under-devotion,” but rather “over-devotion” to his God. He becomes depressed whenever he slips below the high-water mark of his progress in duty, no matter how little that slip may be.

The city causes a heightened sense of failure in Hopkins during the period of these sonnets' creation. The "Terrible Sonnets,” therefore, illustrate the City’s ability to suffocate even the pious and those eager to devote themselves to the cause of humanity. The city lowers the estimation of Humanity even in the eyes of Hopkins, who devotes his life to loving it. The city turns even the most innocent and loving of individuals into a cynical loather of humanity at times.

We can with certainty claim that Hopkins would never write the "Terrible Sonnets” if he avoided the metropolises of England and Dublin. If he stayed in St. Beuno’s, we would remember him for a catalog of poems akin to “Spring” and “Pied Beauty.” Inspired by the splendor of nature around him, he would produce innocent, carefree poems uncritical of himself or humanity. Hopkins' constitution would benefit from a life devoid of the city and devoted to nature. The English literary canon, however, would suffer.

Works Cited:

- Abrams, M.H [ed.]. The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume Two. 6th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1993.

- Bergonzi, Bernard. Gerard Manley Hopkins. New York: Collier Books, 1977.

- Bristow, Joseph. “’Churlsgrace’: Gerard Manley Hopkins and the workingclass male body." Victorian Poetry 59(1992):693-711.

- Clausen, Christopher. “Whitman, Hopkins, and The World’s Splendor.” The Sewanee Review 105(1997): 175-88.

- Daly, Mary. “Dublin in the 1880’s.” The Hopkins Quarterly 14(1987-1988): 95-103.

- Ellis, Virginia Ridley. Hopkins and the Language of Mystery. London: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

- Harris, Daniel A. Inspirations Unbidden: The‘Terrible Sonnets" of Gerard Manley Hopkins. University of California Press: Berkeley, 1982.

- Hopkins, Gerard Manley. Correspondence of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Richard Watson Dixon. Edited by Claude Colleer Abbot. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ---. Further Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Including his Correspondence with Coventry Patmore. Edited by Claude Colleer Abbot. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ---. Journals and Papers of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Humphrey House and Graham Storey. 2nd ed. London: 1959.

- ---. Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges. Edited by Claude Colleer Abbot. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ---. Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Charles Williams. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1937.

- ---. Sermons and Devotional Writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Christopher Delvin, S.J.. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

- MacKenzie, Norman H. A Reader's Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins. Thames & Hudson: London, 1981.

- Martin, Robert Bernard. Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Very Private Life. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1991.

- Roberts, Gerald. “Hopkins and The Conditions of England.” The Hopkins Quarterly 14(1987-1988): 112-126.

- Thesing, William B. “Gerard Manley Hopkins’ responses to the City: The ‘composition of the crowd.’” Victorian Studies 30(1987): 385-408.