Speaking of his “Terrible Sonnets,” Gerard Manley Hopkins suggests in a letter that “if ever anything is written in blood one of these is” (Bridges 219). The poems recount Hopkins' tumultuous examination of the pain and ambivalence that defines his existence. The “Terrible Sonnets” tempt uncritical readers into inaccurate Job comparisons. Hopkins does not wrestle with his faith in God. Hopkins’ merciless interrogations reflect not a loss of faith in God, but an indignation towards his and Humanity’s gross failure to live up to God’s greatness (Ellis 242).

The “Terrible Sonnets" do not capture an “attack” against God for some perceived “transgression” but rather depict a lambaste against modem urban life and degeneracy. Constant exposure to the city-spawned dregs of humanity incites Hopkins to lose faith in the greatness of his fellow man. A Jesuit priest must esteem and empathize with mankind. Hopkins’ inability to do so institutes feelings of failure within him and sends him into a spiral of maddening depression. This depression at his and humanity’s perceived failings in the eyes of God, and not any loss of faith in God on his part, motivate his “Terrible Sonnets.”

The Squalid City

Gerard Manley Hopkins finds metropolitan life repugnant. He tersely conveys his view of London to a friend, Paravicini, when he calls it “a hellhole” (Martin 325). Dublin fares no better in Hopkins’ esteem. He tells another friend, Bridges, that he finds Dublin “as smoky as London, and covered in soot” (368). Hopkins sees Dublin “in a deeply dispiriting state of decline” (366), bearing “the signs of years of neglect” when he arrives (Bergonzi 125). Martin writes of:

patrician Georgian townhouses [that] had declined into squalid congeries of rooms in each of which lived an entire family... a woman might be giving birth on a newspaper-covered bed, surrounded by eight or ten other children intent on their play beneath the swags of an ornately plastered ceiling. It was the kind of contrast that shocked the sensibilities of the tender-hearted Hopkins and provoked him into both sympathy and rage. After his death [sic] his sister told Bridges that ‘he was made miserable by the untidiness, disorder and dirt of Irish ways, the ugliness of it all’ (368)

The untidiness and dirt of Irish ways results in an “...appalling death rate...which had been so bad that many country families were afraid to visit there” (369). While contagions hit the poor living amidst overcrowded squalor the hardest, even the higher classes suffer huge casualties. Daly states, “mortality among the professionals and middle classes seems to have been considerably above the levels prevailing at this time in English cities” (98). Martin attributes the High incidence of mortality in Dublin to the “poor sanitation of practically all the houses” (Martin 369). City health and engineering officials report the “appalling state of house drains, not just among the poor, many of whose houses lacked any sewage system at all, but among the more prosperous classes” (Daly 98). Hopkins lives in a residence with a basement “full of filth and rats, two of which found their way into the stew-pot in the kitchen on one occasion” (Martin 371).

The city depresses Hopkins. He writes to Bridges:

The state of the country [England] is indeed sad, I might say it is heartbreaking, for I am a very great patriot. Lamentable as the condition of Ireland is, there is hope of things mending, but the Transvaal is an unrelieved disgrace. And people do not seem to mind (Bridges 131)

Elusive Muse

But Hopkins faces more than just literal death in the city. Hopkins' city also leads to creative death. Hopkins finds that his “muse eludes [him] in urban physical surroundings” (Thesing 386). Martin reiterates verbatim at two points of his biography that Hopkins feels “dried out by cities, spiritually and poetically” (325 & 335). Hopkins discovers that “urban work and poetic creation seem to be antagonistic or at best mutually exclusive” (Thesing 388). The “horrible place,” the city, exists to “stifle” creative endeavors (Bridges 126).

Thesing says “the city represents [to Hopkins] recalcitrant material opposed to the creation of poetry” (389). Hopkins supports Thesing’s conclusion when he comments: “Liverpool is of all the places the most museless. It is indeed a most unhappy and miserable spot” (Correspondence 42). Ideas for poems germinate in Hopkins' mind, yet somehow the city parasitically sucks away the energy necessary for their manifestations. Any poem Hopkins mentions “in the course of its composition would never be finished... he had more than enough imagination for a dozen poets and scarcely the energy for one” (Martin 331).

Nature and the Divine

The vampiric city must feed off the lifeblood of nature to flourish. Developers must either entirely raze nature to make room for a city or instead portion Nature into controllable cells. The lack or destruction of nature brings pain to Hopkins, who says “I always knew in my heart Walt Whitman’s mind to be more like my own than any other man’s living” (Bridges 155). The Jesuit Priest emphasizes that, while he disagrees with Whitman’s homosexual tendencies, he feels a kinship with the American poet thanks to Whitman's passionate views on nature (155).

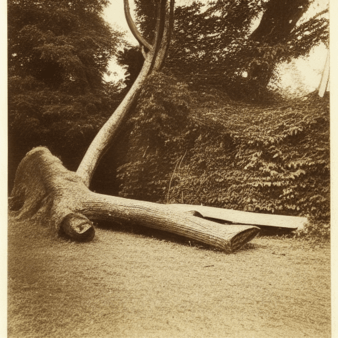

The felling of trees nearly spurs Hopkins to suicide, thanks to “his sense of the impossibility of ever making amends for destruction or of replacing any object or created thing, since the inscape of each made it literally irrecoverable” (Martin 306). In The Journals and Papers of Gerard Manley Hopkins, he writes:

The ashtree growing in the comer of the garden was felled. It was lopped first: I heard the sound and looking out and seeing it maimed there came at that moment a great pang and I wished to die and not see the inscapes of the world destroyed any more (230: Italics mine)

St. Beuno’s surrounds Hopkins with more nature than any locale and thus fills him with “unusual happiness” (Martin 261). While staying in St. Beuno’s, he “walk[s], fishe[s] and wr[ites] poetry” (268), and takes in the “lovely sights” of “a flock of seagulls wheeling and sailing high up in the air, sparkles of white as bright as snowballs in the vivid blue” (Further 157).

The nature around him provides a great muse and drives him to write “approximately one third of all his mature poetry” (Martin 261). This period of his life marks copious poems that celebrate the wonders of Nature. For example, in “Spring,” he writes “Nothing is so beautiful as Spring / When weed, in wheels, shoot long and lovely and lush; / Thrush’s eggs look little low heavens...” (1-3).

Notice how Hopkins compares “eggs” to “heavens” (3). On the surface, eggs look like clouds, or “low heavens” (3). But Hopkins’ choice of the word heaven over a secular synonym implies a patent connection between God and Nature. Hopkins, during this period of his life, feels a connection between God and nature. Hopkins embraces the connection between God and Nature without question. He sees no need for burdening skepticism or deconstruction.

Martin writes, “almost more than at any other time in his career, [Hopkins] seems totally at home with the connection of God and nature, content to accept and praise it without, as Keats almost said, any irritable reaching after fact and reason. To put it in Hopkins’ own terms, he never seems to have been so happily engulfed in unquestioning faith” (262: Italics Mine). Hopkins equates God and Nature in “God’s Grandeur,” when he writes “the world is charged with the grandeur of God” (1) and says that “nature is never spent” because “the Holy Ghost over the bent / World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings” (13-14). Since Hopkins believes in a connection between Nature and God during this period in his life, an attack against nature presents obvious, grander implications.

Over time, the relationship between nature and the divine evolves and becomes more complex for Hopkins. Instead of seeing a “one-to-one” mapping between Nature and God, he sees in Nature a functionary analogous to rosary beads or holy water. Hopkins sees in Nature a divine element that can atone for Humankind’s sins. He sees Nature “[wipe] out in daily reassertion of the sanctity of the external [natural] world” Humankind's “worst ravages, moral and physical” (Martin 303).

Hopkins believes that decent men must appreciate and embrace the redeeming qualities of nature. Unfortunately, repeated contempt by men towards nature starts to make it difficult for Hopkins “to be confident that man could not ruin the world” (304). Clausen writes, “ecological destruction" indicates to Hopkins, “a symptom of human depravity” (184). The city, and its killing of nature, therefore, indicates Man’s ability to be contemptuous towards a divine mechanism.

Man, the Animal

The city reduces Mankind in Hopkins’ estimation on multiple levels. To Hopkins, the vice-like city squeezes humanity, the most beautiful and dignified creation in the universe, into a lesser animalistic being.

Hopkins sees the city degrade men on spiritual, intellectual, and physical planes. These observations lead Hopkins to lose his hope for humankind.

Spiritually speaking, the city breeds human degeneracy and filth. Its suffocating machinations destroy the would-be pious, allowing the immoral weeds of humanity to flourish. Hopkins’ city experiences include a string of exposures to the most base products of the modem city. These patterns of depravity sap both his faith in humanity and desire to live. He writes:

My Liverpool and Glasgow experience laid upon my mind a conviction, a truly crushing conviction, of the misery of town life to the poor and more than to the poor, of the misery of the poor in general, of the degradation even of our race, of the hollowness of this century’s civilization: it made even life a burden to me to have daily thrust upon me the things I saw (Correspondence 97: Italics Mine)

The “things” that Hopkins “sees” constantly in the city include unloved, disheveled children, prostitutes, and an array of public displays of immorality. Near his Oxford residence lies “an oasis in which was to be found ... children begging or selling matches” and “omnipresent tramps and drunks” (Martin 369).

His time in Dublin exposes him to “...the depths of the city’s poverty and deprivation” (Daly 97). Daly deems Hopkins' Dublin locale “the worst tenement area in the city, a haunt of prostitutes serving the nearby Dublin Castle garrison, containing innumerable public houses” (97).

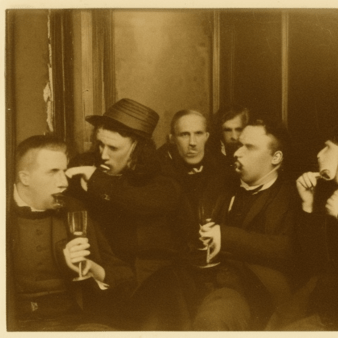

Hopkins’ letters during his city residence “...convey the sense that, in the city, moral degeneracy is out of control” (Thesing 388). The alcohol consumed by working-class residents contributes to runaway degeneracy. Hopkins believes alcohol causes immorality amongst city-dwellers because:

it makes the man a beast: it drowns noble reason, their eyes swim, they hiccup in their talk, they gabble and blur their words, they stagger and fall and deal themselves dishonourable wounds, their faces grow blotched and bloated, scorpions are in their mind, they see devils and frightened sights (Sermons 42)

Hopkins witnessed alcoholic gluttony in both Dublin and Liverpool. “Liverpool sent him away with a memory he kept for years, of the church organist who got drunk at the organ and was dismissed” (Martin 333).

In addition to drunkenness, the “undisciplined habit of workmen spitting on the public pavements” taints Hopkins’ dignified view of humanity (Thesing 388). Hopkins writes to his contemporary Robert Bridges:

Spitting in the North of England is very, very common with the lower classes: as I went up Brunswick Road (or any street) at Liverpool on a frosty morning it disgusted me to see the pavement regularly starred with the spit of the workmen going to their work; and they do not turn aside, but spit straight before them as you approach, as a Frenchman remarked to me with abhorrence and I cd. only blush. And in general we cannot call ours a cleanly or a clean people: they are not at all the dirtiest and they know what cleanliness means, as they know moral virtues, but they do not always practise it (Bridges 299)

As Thesing writes, “the moral and social degeneracy that he sees in groups of urban people, especially working class people” incenses Hopkins (388). Moral degeneracy in the city, however, transcends the physically indulgent and repugnant actions of the vulgar class.

Hopkins also witnesses questionable actions taken by “the dominant Catholic middle class in the city” (Daly 100). Many of the men who compose this class of respectable and politically active businessmen make their money by “exploiting the city’s poor” (Daly 100). Hopkins even sees an intellectual peer of his exploiting the poor for monetary gain. Daly calls Bryan O’Looney, a professor of Irish at Hopkins’ university in Dublin, “possibly the largest tenement owner in the city” and undoubtedly “the most persistent violator of public health regulation” (100). Roberts says that the constant viewing of “...man, the pride of God’s creation... declined into unredeemed materialism” weakens Hopkins’ sensitive constitution (119).

Hopkins also witnesses intellectual decline in the city. Hopkins loves learning for its own sake. Unfortunately, when he tries to impart this love for knowledge to his Dublin students, he learns that the “facts that they could repeat in examinations” interest them more than “the play of the intellect” (Martin 375). The city, or more accurately a product of the city, “the small rising Irish middle class,” holds a “utilitarian attitude to education... as a passport to careers and respectability.” This attitude kills the desire for a liberal education amongst Hopkins’ students. Daly writes “intellectual curiosity in the classics was the preserve of [but] a few” (102). Martin writes “luminous idealism ...had long since evaporated” in the classroom, with “Irish politics now seem[ing] more important than Greek philosophy or even Christian theology” (375).

Hopkins’ students see no utility in his classical subjects and feel “no compulsion to listen to him,” instead “talk[ing], laugh[ing] and creat[ing] a constant disturbance” (Martin 376). The students have so little respect for Hopkins and his intellectual endeavors that they actually drag him “around the table by his heels to demonstrate Hector’s fate at Troy” (377).

Hopkins tries to maintain his humility in this situation but “object[s] to them being rude to their professor and a priest” (Bergonzi 128). The apathy of his students and their parents fortifies his bleak opinions of humanity.

The city also produces a physical decline in the modem man, which angers Hopkins. He writes:

What I most dislike in towns and in London in particular is the misery of the poor; the dirt, squalor, and the illshapen degraded physical (putting aside moral) type of so many of the people, with the deeply dejecting, unbearable thought that by degrees almost all our population will become a town population and a puny unhealthy and cowardly one (Further 293)

Bristow states that Hopkins “adores the male body,” thereby explaining Hopkins’ indignation at its reduction (695). He also says how Hopkins equates something of the divine in a muscular body, stressing how Hopkins has “concern with the spiritually enhanced muscularity of the laborer” (695).

Modem man’s failure to live up to his potential physically, spiritually, and intellectually reduces his worth in Hopkins’ eyes. A letter to Robert Bridges, recounting his feelings during a parade of horses in Liverpool illustrates his disgust towards modem man. Hopkins writes, “while admir[ing] the handsome horses I remark for the thousandth time with sorrow and loathing the base and bespotted figures of the Liverpool crowd... as I look about them it fills me with shame and wretchedness” (Bridges 127-8). An often-quoted letter to bridges best illustrates Hopkins' view of modern man. He writes “the drunkards go on drinking, the filthy, as the scriptures say, filthy still; human nature is so inveterate. Would that I had seen the last of it" (Bridges 126).

Works Cited:

- Abrams, M.H [ed.]. The Norton Anthology of English Literature: Volume Two. 6th ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1993.

- Bergonzi, Bernard. Gerard Manley Hopkins. New York: Collier Books, 1977.

- Bristow, Joseph. “’Churlsgrace’: Gerard Manley Hopkins and the workingclass male body." Victorian Poetry 59(1992):693-711.

- Clausen, Christopher. “Whitman, Hopkins, and The World’s Splendor.” The Sewanee Review 105(1997): 175-88.

- Daly, Mary. “Dublin in the 1880’s.” The Hopkins Quarterly 14(1987-1988): 95-103.

- Ellis, Virginia Ridley. Hopkins and the Language of Mystery. London: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

- Harris, Daniel A. Inspirations Unbidden: The‘Terrible Sonnets" of Gerard Manley Hopkins. University of California Press: Berkeley, 1982.

- Hopkins, Gerard Manley. Correspondence of Gerard Manley Hopkins and Richard Watson Dixon. Edited by Claude Colleer Abbot. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ---. Further Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins, Including his Correspondence with Coventry Patmore. Edited by Claude Colleer Abbot. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ---. Journals and Papers of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Humphrey House and Graham Storey. 2nd ed. London: 1959.

- ---. Letters of Gerard Manley Hopkins to Robert Bridges. Edited by Claude Colleer Abbot. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- ---. Poems of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Charles Williams. 2nd ed. London: Oxford University Press, 1937.

- ---. Sermons and Devotional Writings of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Edited by Christopher Delvin, S.J.. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

- MacKenzie, Norman H. A Reader's Guide to Gerard Manley Hopkins. Thames & Hudson: London, 1981.

- Martin, Robert Bernard. Gerard Manley Hopkins: A Very Private Life. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1991.

- Roberts, Gerald. “Hopkins and The Conditions of England.” The Hopkins Quarterly 14(1987-1988): 112-126.

- Thesing, William B. “Gerard Manley Hopkins’ responses to the City: The ‘composition of the crowd.’” Victorian Studies 30(1987): 385-408.